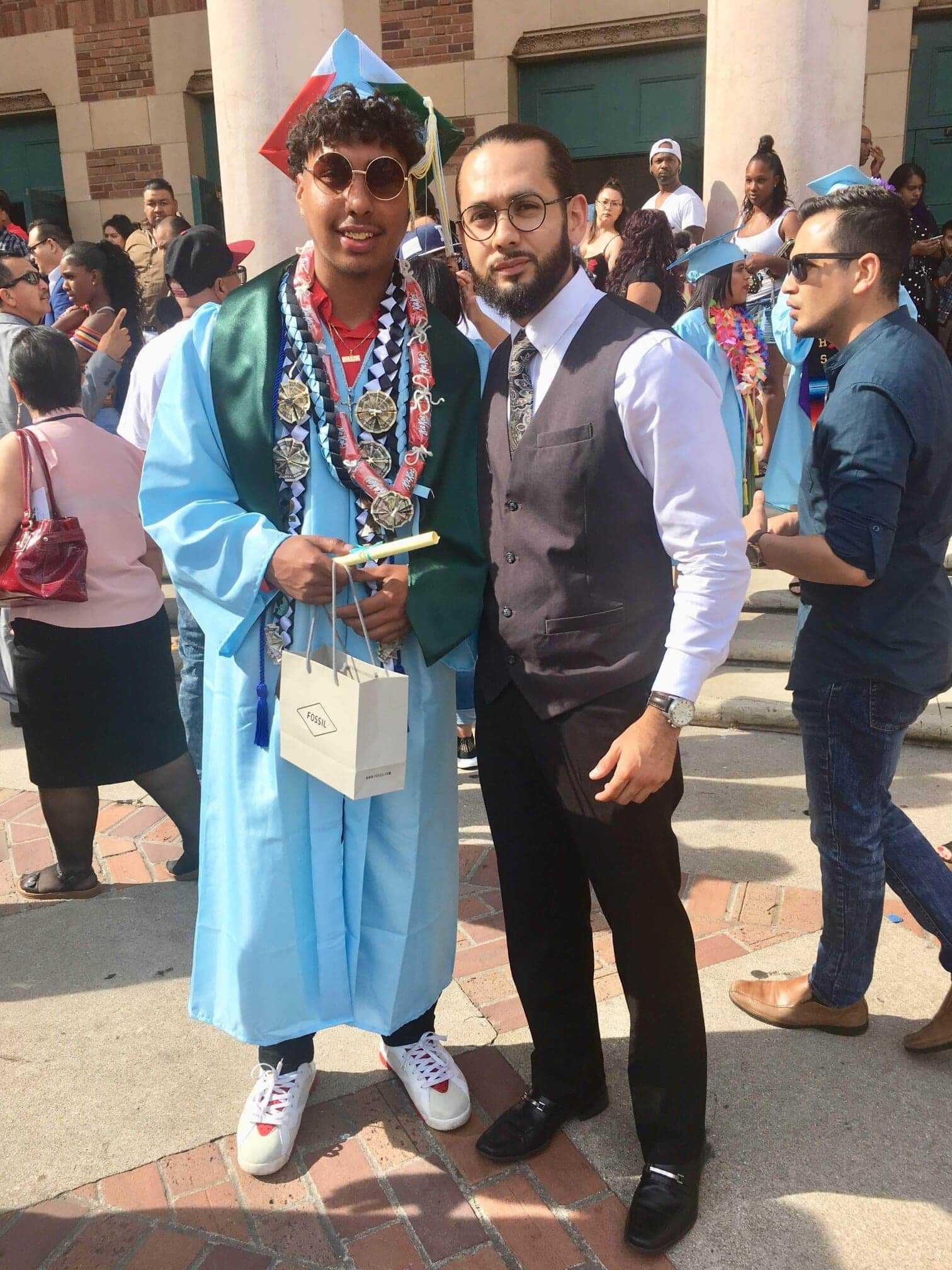

Christian Landa

Program Manager

Improve Your Tomorrow (IYT)

The following excerpt was written by Christian Landa. Read his reflection of the journey that motivates his commitment to equity-driven leadership.

One aspect that has guided my commitment to equity-driven leadership in general, and racial justice leadership in particular, is the notable absence of people of color in teaching positions. When considering how much time a young person spends in the classroom, they will likely form a bond with a teacher. However, when we consider that in “high-poverty” elementary and secondary schools only 16% of educators are black, 17% are Hispanic, and 63% are white on average, we can assume that young men and women of color will find it difficult to identify with an educator, causing unwanted and typically unwarranted resentment to school in general (ref. The State of Racial Diversity in the Educator Workforce U.S. Dept of Ed. P. 6). We know the effects of neglecting school can be harmful, often irrevocable, and ultimately feeds into the school-to-prison pipeline.

While in middle school and through my sophomore year in high school, I was often scrutinized and made an example of for my peers. Unintentionally, I would make myself an easy target by provoking my teachers. I would emulate the same attitudes that other young black and brown men and women had towards them. As a Latino, I connected with whom I saw in my community, hoping to fulfill this need to be included, trying to balance the role of the potential first-generation college graduate, while not leading on to the fact that I actually enjoyed learning, because it was not the thing to do as a young man of color. I did not have a positive role model in my life that wasn’t also working manual labor, or involved in a get-rich-quick scheme, or spent their evenings wishfully thinking but never truly putting pen-to-paper to establish a plan. In short, educators never seemed to me to be an ally of any kind, and because I was repeatedly met with belittling remarks, I concluded that teachers did not care. In retrospect, this is obviously not true; fortunately, my middle school English teacher, Mrs. Frazier, was one of the first individuals to ever challenge my integrity both as a young man and a student, by calling me out and having a personal conversation with me about my role as my mother’s first son and a fatherless young man who was susceptible to being locked up because of his skin color. Mrs. Frazier was not Black or Latina, but I ask myself: “How much more sooner would I have realized the deeply positive effects a teacher plays in the lives of their students, if that conversation had been with a person who looked like me?”

Currently, my role as a program director and mentor puts me side-by-side with young men of color who may also be lacking a positive role model in their life. I have the opportunity and the privilege to help mold these young men into men of honor and leaders who shape their community by taking pride in their academic endeavors because their mentors also excelled in higher education.

“ “A man is worked upon by what he works on. He may carve out his circumstances, but his circumstances will carve him out as well.””